Would you be cool with living without air conditioning?

How did people manage without air conditioning? A classic question, especially during the hot weather. Well, they managed. And much better than we do.

July 2023 was the warmest month in the history of temperature measurements. China recorded a record 52.2 degrees C, Sardinia – 48.2 degrees C. The record of heat (the world’s average air temperature was calculated) was documented on July 3 and was quickly broken in the following days.

That’s the way it’s going to be, scientists say, because the inhuman heat is just one of the manifestations of global warming. Hence we will be breaking more records and seeking any source of coolness more and more.

What instantly comes to mind? Air conditioning. We install it at work, at home, in the car, in the store, in the hotel where we spend our vacations. It’s becoming increasingly difficult to imagine life without it, forgetting that it’s a relatively new invention. The term “air conditioning” was first used in 1906. Four years earlier, the first device was installed to cool and maintain adequate humidity. In a public building – one of New York’s theaters – the first air conditioner appeared in 1925. It became widespread after World War II, with advances in technology and the production of compact devices that were installed by the windows.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that there are two billion air conditioning units in the world. Eurostat adds that air conditioning use has increased in the European Union over a 40-year period (1979-2021). The European Statistical Office uses an indicator called “cooling degree days” (the product of days and degrees). In 1979 it was 37, in 2021 – 100. The hotter it gets in the summer, the more cooling devices we’ll buy. According to the IEA, in 2050 air conditioners could become mandatory equipment for every home.

As you can easily imagine, the increased demand for cooling comes with higher power consumption. The IEA cites an example from Texas: a 1-degree increase in air temperature above 24 degrees Celsius carries a 4 percent higher demand for electricity. Globally, about 10 percent of the energy cake is eaten up by cooling. In some places, the energy consumption on hot days increases by 70 percent compared to cooler months. Not surprisingly, there is always a risk of blackouts in the summer.

And this is how, by burning fossil fuels, we heated up our planet. Now we’re burning them to cool down. Scientists have calculated that air conditioning emits nearly two billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. That’s nearly 4 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

How do we get out of this vicious cycle? By redesigning the mindset in which the air conditioner is the only protection against the heat. By designing buildings differently and planting greenery.

To catch the wind

It’s worth learning from the experiences of cultures that had to deal with high temperatures before air conditioners were even invented.

The author of this text has spent several extremely hot days in Marrakech, Morocco. The temperature exceeded 40 degrees. She lived in a riad – a traditional Moroccan house designed for a multi-generational family. A typical riad is a several-story building, the central part of which is a courtyard. Around it are galleries, from each of which there are entrances to different rooms. Windows face the shaded courtyard and are additionally covered with shutters. Many buildings have no windows at all on their facades or they are small

– all to let as little sun and heat as possible enter through them. They are protected from them by thick walls, and coolness is also provided by stone or ceramic tiled floors and walls. The courtyard often has a fountain or an ornamental pool, other temperature-reducing elements, as well as plants.

In the July heat, the riad, even without air conditioning, provided a pleasant coolness.

In Morocco, like in other Arab countries, windows or balconies are sometimes obscured by decorative wooden grilles. The mashrabiya is meant to provide privacy, but most importantly to protect from the sun while allowing light to pass through. It catches the wind and ensures adequate humidity indoors. Similar solutions can be found in other cultures, for example, in India it is found under the name jaali.

Mashrabiya, for example, inspired the designers of Al Bahr Towers, two 1 How did people manage without air conditioning? A classic question, especially during the hot weather. Well, they managed. And much better than we do.

July 2023 was the warmest month in the history of temperature measurements. China recorded a record 52.2 degrees C, Sardinia – 48.2 degrees C. The record of heat (the world’s average air temperature was calculated) was documented on July 3 and was quickly broken in the following days.

That’s the way it’s going to be, scientists say, because the inhuman heat is just one of the manifestations of global warming. Hence we will be breaking more records and seeking any source of coolness more and more.

What instantly comes to mind? Air conditioning. We install it at work, at home, in the car, in the store, in the hotel where we spend our vacations. It’s becoming increasingly difficult to imagine life without it, forgetting that it’s a relatively new invention. The term “air conditioning” was first used in 1906. Four years earlier, the first device was installed to cool and maintain adequate humidity. In a public building – one of New York’s theaters – the first air conditioner appeared in 1925. It became widespread after World War II, with advances in technology and the production of compact devices that were installed by the windows.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that there are two billion air conditioning units in the world. Eurostat adds that air conditioning use has increased in the European Union over a 40-year period (1979-2021). The European Statistical Office uses an indicator called “cooling degree days” (the product of days and degrees). In 1979 it was 37, in 2021 – 100. The hotter it gets in the summer, the more cooling devices we’ll buy. According to the IEA, in 2050 air conditioners could become mandatory equipment for every home.

As you can easily imagine, the increased demand for cooling comes with higher power consumption. The IEA cites an example from Texas: a 1-degree increase in air temperature above 24 degrees Celsius carries a 4 percent higher demand for electricity. Globally, about 10 percent of the energy cake is eaten up by cooling. In some places, the energy consumption on hot days increases by 70 percent compared to cooler months. Not surprisingly, there is always a risk of blackouts in the summer.

45-meter-high skyscrapers in Abu Dhabi. Here, the architects proposed facades that resemble connected umbrellas in appearance. The glass structure reacts to the sunlight, closing and opening depending on its intensity.

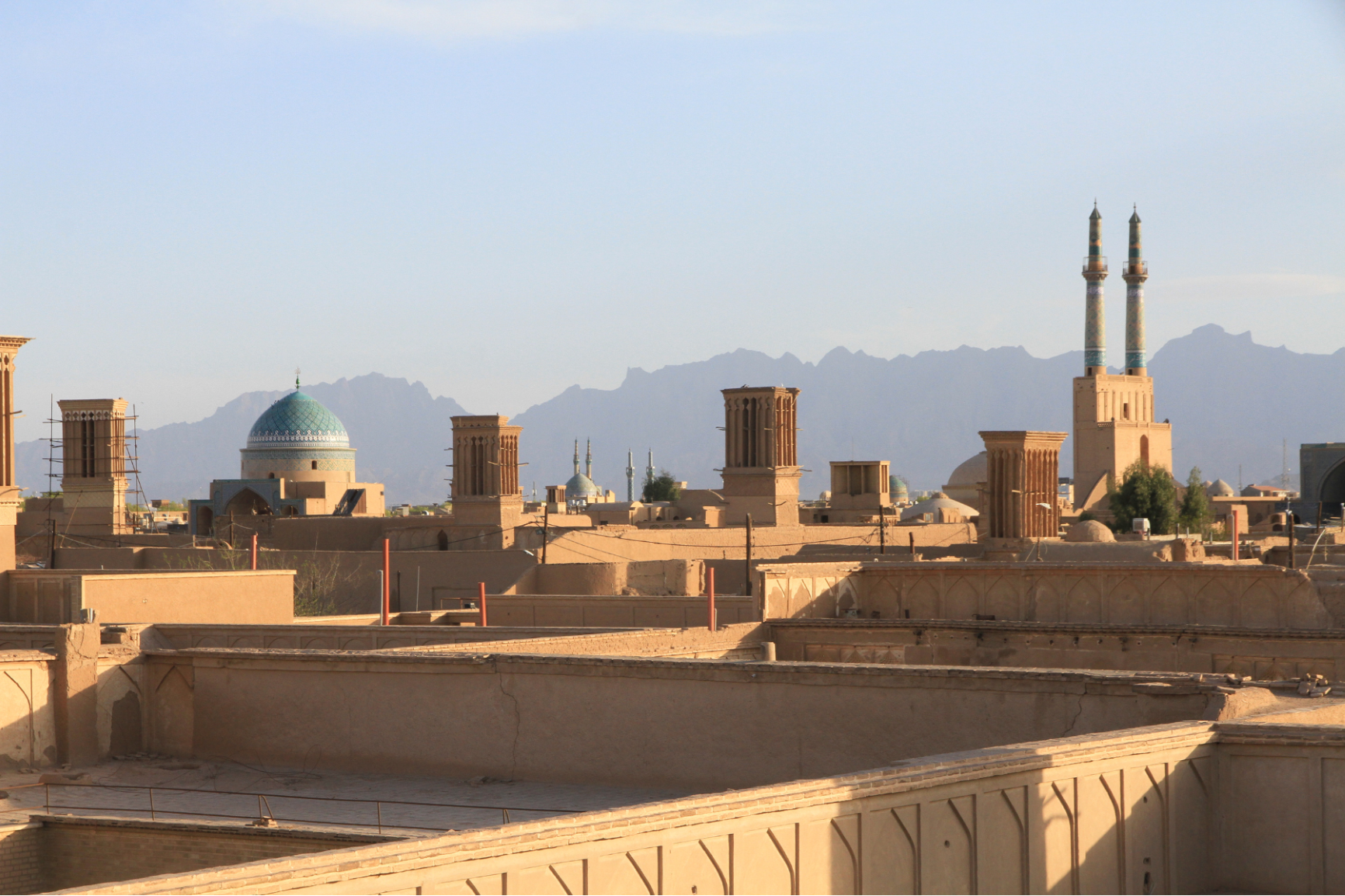

In the Middle East, especially in what is now Iran, some houses have distinctive towers with oblong openings on top. These are wind catchers (pictured), called bagdir in Iran (most can be found in the city of Yazd). They provide air circulation inside the building, acting on the principle of gravity ventilation. Cooler air flows through their openings, entering the building, pushing out warm air (it’s lighter). In this way, the interior temperature can be lowered by up to 10 degrees C.

Let’s plant some trees

Speaking of water, don’t forget that plants collect it and then evaporate it, especially trees. One full-grown tree can release 300 to 500 liters of water into the atmosphere, and thus reduce the air temperature in its vicinity by about 3.5 degrees C. If trees in cities are strategically placed, they can reduce the temperature by as much as 8 degrees. Not to mention that they physically protect us from the sun by providing shade.

The work of one tree can be compared to the activity of 10 air conditioners. The U.K. Office for National Statistics calculated that London saved £5 billion on air conditioning between 2014 and 2018 thanks to trees growing along the streets. An additional 11 billion in savings came from reducing the drop in productivity in high temperatures.

However, let us emphasize that we are talking about mature, healthy, large trees, which – unfortunately – don’t have an easy life in cities (we’re restricting their access to water, for example). To replace one healthy 100-year-old beech tree (in terms of the work it does for us), we would have to plant about 2,700 trees with a crown diameter of up to 1 meter.

Greenery reduces the effects of so-called “urban heat islands,” i.e. excessive heating of urban areas, which are slow to release heat into the atmosphere. The temperature in the city center is usually higher than that in the suburbs, because there is nothing to evaporate from concrete on the streets. That’s why every tree and every patch of greenery is so important. These can also be “green” walls and roofs on bus shelters, for example. Installing these can reduce the temperature under the shelter by 3-5 degrees.

How they do it in Vienna

The Austrian capital, like many cities around the world, is trying to reduce the urban heat island effect, prepare for the even higher temperatures that threaten us in the future, and take care of the health and well-being of its residents. Less concrete, more greenery – that’s how the city’s program can be summarized. Among other things, it includes planting large trees, investing in green walls and roofs, replacing pavement with permeable surfaces, installing hydrants with drinking water connections (also for dogs) or benches in shady areas.

Officials have created a design for a network of “cool streets” that will be planted with trees. These are not randomly chosen locations. They were selected by climatologists, bearing in mind the potential impact on the microclimate of the neighborhood. One street in the center was shut down and turned into an Else Feldman Park. Dozens of trees and shrubs were planted on 3,700 square meters, and alleys for pedestrians and cyclists were laid out.

The plan also includes so-called “cool spots” in parks and squares. For now, two prototype ones have been created in Esterhazypark and the Schlingermarkt market. These are shaded and planted small spaces where “climate trees” have been placed. They spray a mist, causing the temperature in the “cool spot” to be 6 degrees lower than in the neighborhood.

The right air temperature is important, but so is air quality. At Łukasiewicz – PIT, we conduct indoor air quality tests. They consist in determining formaldehyde and VOC emissions from wood-based materials, building materials and products used for interior furnishings. Details here.